Three Times A Lady: Artist Dan Fischer's Love Triangle

Dan Fischer, Weegee Warhol, 2006

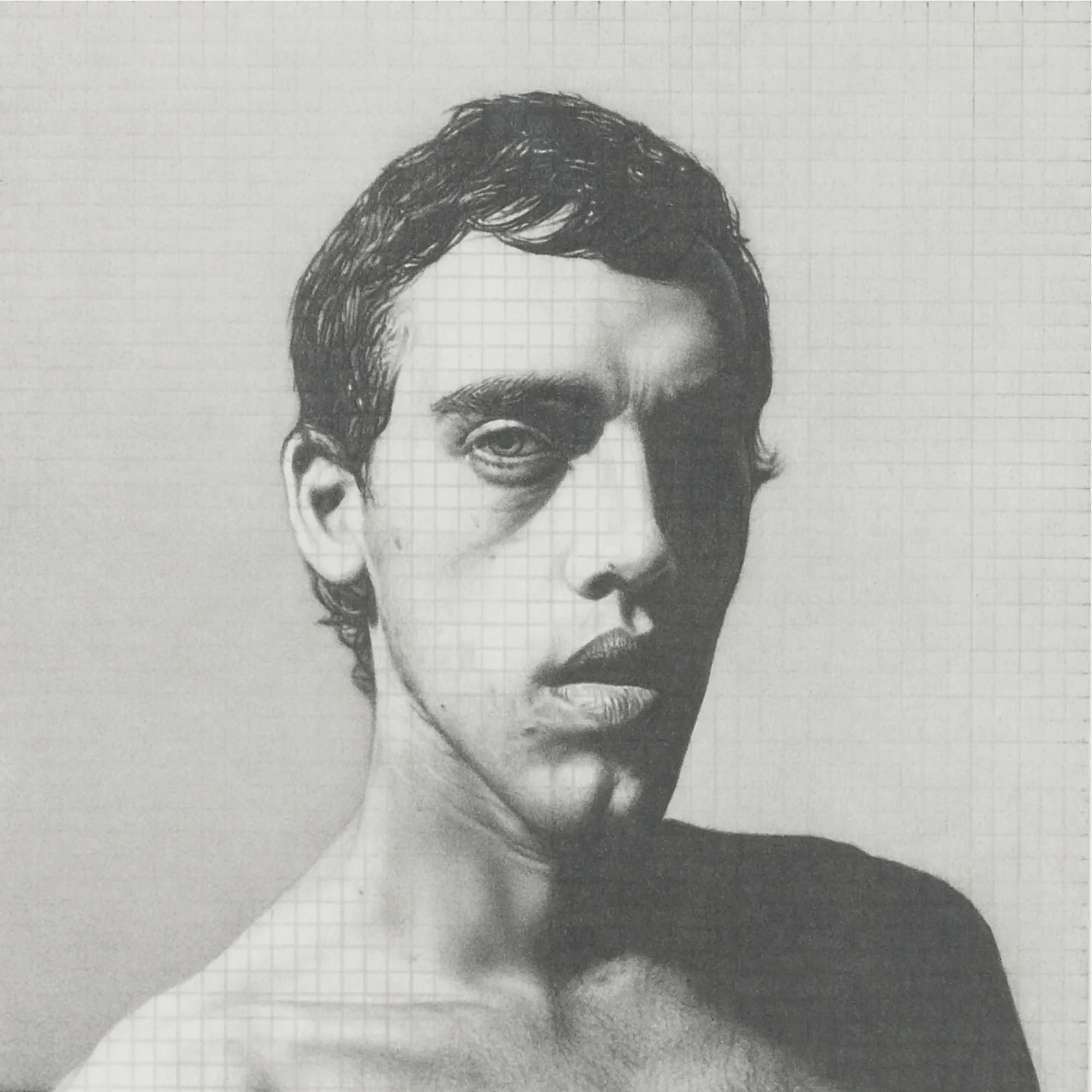

Dan Fisher’s Weegee Warhol is a moderately sized drawing of photographer Weegee’s Polaroid portrait of pop icon Andy Warhol. Located in Atlanta’s renowned High Museum of Art, Fisher’s delicately intricate piece initially appears to be a silver gelatin print, which draws the viewer in to realize that the image is in actuality a graphite on paper work paying homage to mechanical reproduction and appropriation. The warped clone like portrait of Warhol finding its origin on a standard sheet of 13x10 inch Stonehenge paper is brought to life by Fishers technically masterful hand using only the raw capabilities of HB lead in a mechanical pencil. Finding his starting point through his love of art and their creators, Fisher sorts through numerous images before choosing one picture that connects him to his own intrinsic nature as an artist. Once a selection has been made he then takes the copy of the work and Xeroxes another copy from the secondary source to consume and reproduce himself.

As with his other works Weegee Warhol features a light, yet prominent 1/8” grid left visible on the artwork functioning as a grounding point for the medium while the acknowledging the grueling process that signifies Fishers drawings. The artists’ hand denies any implication of abstract freedom maintaining all of the photographic eccentricities noted in Weegee’s original work. The mixture of strong and soft lines converge seamlessly suggesting a perfect layer that reveals an equally flawless tonal range of grey and photorealist effects. The shading and shadows within the drawing create an impeccable mass adding movement to the implied lines over the grid that already appears. The open form white space purposely left around Warhol respectfully follows its inspiration and ties Fishers practice to their photographic beginnings.

What’s most impressive is Fishers ability to create depth and detail within the work through his use of lightness and darkness. This is no doubt due his teachings with artist Andrew Deutsch at Alfred University in his home state of New York. It was this experimental drawing course that essentially introduced Fischer to the realistic side of what drawing could achieve. Using John Cage’s “series of pre-compositional strategies” to inform his students, Deutsch pushed Fischer to see drawing in terms of scanning patterns specific to the lines on the first television sets. This elaborate process and “love hours” that Fisher spends on his works is undoubtedly the distinctive touch and velvet texture that catches the eye of any passerby.

Further explained in Robert Hobbs essay Dan Fischer: Xerox Realism; Fisher’s hallucinogenic reproduction is as he puts it a reproduction of “the idea of reproduction, in relation to the working of mass media in general”. His coined style of Xerox Realism stands to stress the fact that he does not wish to simply reproduce an image but to become closer to the artist and their work. By laboring over the ideas and essence of the original artwork Fischer becomes an onlooker and a fan, an addict of the iconography. Ironically it is this act of voyeurism that directly connects Fisher to Warhol and Weegee, in their theory to practice. Although Fisher’s handmade drawing is not reproducible in the same manner Warhol’s silkscreen prints, or Weegee’s photographic prints replicate. The daunting and lovemaking task of repetitively going over and over the lines of his drawings bring Fischer to the same intimate attachment with his subject matter that both Warhol and Weegee thrived off of during their self-propelled careers.

All three of these New York based artists work and comment on the cultural and social structures of which they also objectively worked within. The complex intertwining of their theories and practices is a direct complimented to Fishers choice of Weegee’s distorted image. Weegee’s Andy Warhol created using textured glass in the enlarger by projecting multiple images of his portrait directly onto the photosensitive paper conveys just as much about the “celebrity” of Andy as it does art in Fishers drawing.

Any reproduction like Weegee Warhol faces scrutiny of authorship attributed to the overlapping meanings and reconstructed nature of its ownership. Yet despite the unavoidable hang-ups of remaking a highly circulated work, Fisher’s artistic practice holds the “artist’s hand” at the forefront of the artwork giving the piece a personal touch lacking in a typical mechanical made copy. As noted in Hobbs essay, even the simple act of slowing down to draw a reproduction is counter intuitive of the quick ready-made way in which most historical reproductions have been produced blending “real with imitation”.

Though one could certainly argue that Fishers work is void of conceptual meaning as it is a copy of a copy. It’s vital to cite that Fisher does not intended to use the thoughts of his idols to add meaning to his mastery of drawing but rather draw attention to his dedication to his craft and their contributions to art. The work would never reach the technical height that sets it apart from other works had his own formidable passion not allowed room to move the work their on its own. Perhaps the unseen meaning of Weegee Warhol is buried underneath the debris and repetition of the artists and iconography preceding it. Hiding the simple yet pure revelation that his artistry forces an audience aware of some previous relevance to look at the drawing as a fresh work rid of the conventions of pop and reproductive art. Disguising and otherwise masterful and successful piece with poetic contradictions.